Structural Slab on Void Forms vs. Conventional, Soil-Supported Slab on Grade

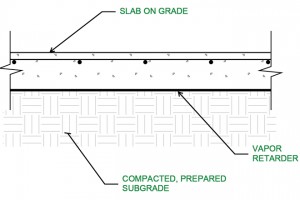

In expansive soil regions, the Geotechnical Engineer for a project usually provides recommendations for grade-level floor construction – structural slab on void forms or conventional slab on grade – based on the existing subgrade properties, excavation depth, and compaction of select fill. The Structural Engineer of Record (SER) then provides a comparative study of both options. Conventional slab on grade is generally a thinner, lightly reinforced slab requiring excavation and replacement of subgrade with a select fill but is subjected to movements as the existing subgrade heaves. In contrast, the structural slab on void form option often requires a thicker, heavily reinforced slab spanning between larger column foundations and other intermediate foundations but without undercutting or removing the existing soil. The void forms allow for placement of wet weight of concrete during construction but absorb ground moisture gradually and lose strength after the concrete has set, thus creating a gap under the slab to allow for soil movements. The final decision by the owners is usually based on the comparison of the initial construction cost of each option without fully understanding the short- and long-term consequences.

…